History of Polish Jews up to 1600’s

The first records of Jews in Poland are dated back to the year 960. Ibrahim ibn Yakub, a Jew from Cordoboa, was sent on a diplomatic mission across Europe. He visited Poland, which he referred to in his writings as “the Land of Mieszko”. (I had to do further research on the meaning behind this name. Mieszko was the ruler of Poland at the time of Ibrahim’s travels.)

As we already know from our class sessions, Jews faced discrimination. However, many Jews migrated to Poland because, in comparison to other parts of Europe, there was a greater sense of “religious tolerance”. Emphasis on tolerance: Jews lived on Polish soil, but they still had to endure prejudice and the sense of religious inequality. When the Black Plague emerged, the Jews were blamed for it. However, the Jews had legal protection, so any negative actions taken against them or their property wouldn’t go unnoticed. (Jewish graveyards in particular suffered, as the graves would be damaged out of spite.)

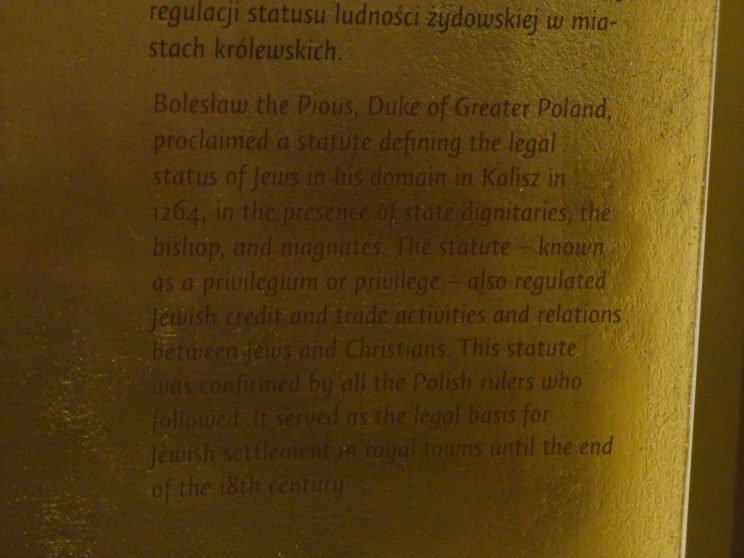

In 1264, Boleslaw the Pious, the Duke of Greater Poland, gave Jews permission to settle on Polish land through a special charter. (In other words: Jews were officially invited to Poland for the first time.) One of the rights granted to them in the charter was the right to govern themselves. The image above describes how trade was regulated. The main occupation for the Polish Jews was as a trader. Gdansk was the main center for trading, and Jews were not allowed to do business there. Conditions gradually improved and the Jews were granted more privileges as time passed.

In the year 1356, King Kazimierz the Great took a Jewish girl as his mistress. Her name was Esther and she is rumored to be the reason for why the king gave the Jewish Poles more privileges. Her story was made famous in religious texts. (There are some differences between the two women, mainly that Esther from the Hebrew Bible has her story take place in Persia, unlike the Esther featured in the museum.)

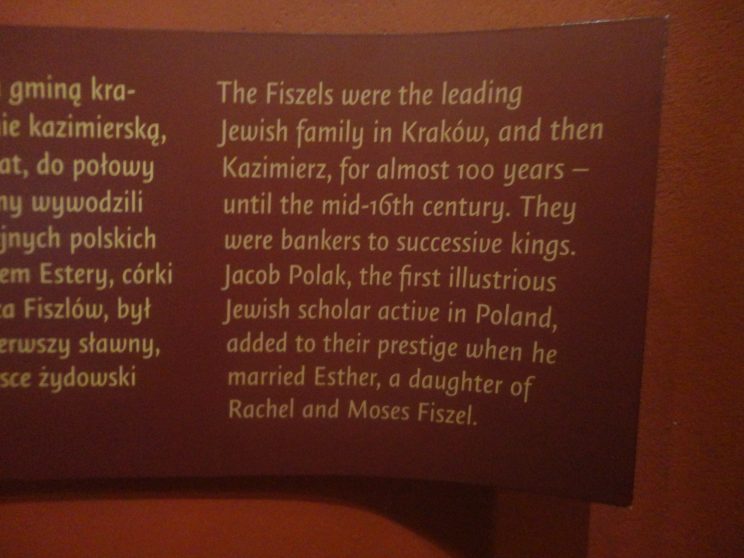

In 1503, Jacob Polak was appointed rabbi by King Aleksander. As we see from the image above, Polak is a very famous Polish Jew. Jews in Poland (and later, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) held very important positions as bankers. At one point, Jews were even bankers for the Polish crown.

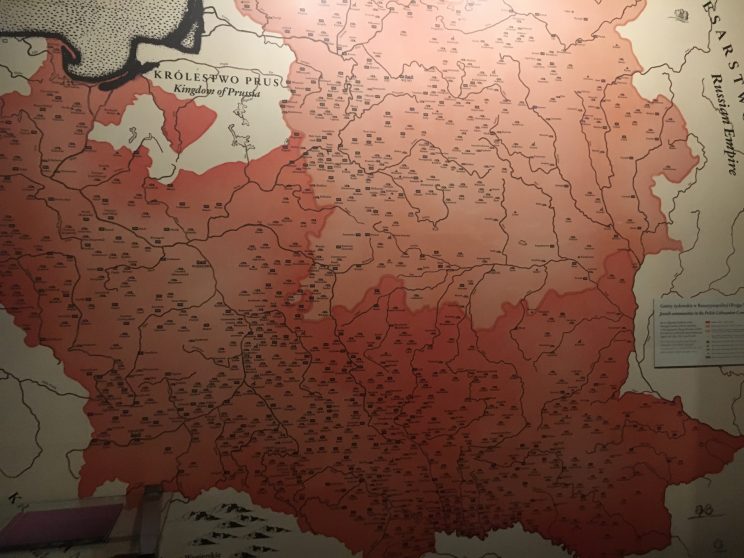

In 1569, the Union of Lublin created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which would become home to Europe’s largest Jewish community.

Maura Kiefer ’19

The Jewish Population of the world has always been a scape goat for many things because of antisemitism through the centuries. Most often the Jewish populations in cities, or countries are blamed for something that is either myth, or that they had n control over, such as occupation since they were restricted heavily.

What this essay is about is the Cossack Uprising in Ukraine in 1648. I first heard about this while in the Jewish museum in Warsaw. There wasn’t very much in the museum about it, but it intrigued me and made me want to find out more of what happened around the event.

In the early part of the 16th century the king of Poland offered economic privileges and some civil rights and privileges to their Jewish population. Because of this, more Jews moved to Poland because in other provinces to the West, they did not have as many rights elsewhere. Because of the migration and that the Jewish population found a good place to make a home for their families and were able to make a reasonable living for themselves and take care of themselves with some stability, the population grew to over a million. This did cause the lower classes to resent them, since they were caught between the nobility, and their wanting to maximize profits, and the peasantry who felt that they were being exploited. Though the nobility tried to pacify them by exempting them from taxes, but it did not work and things only kept getting worse in the relations between the different classes, causing some of the peasants to join the Cossacks when they came to sack the city.

In Eastern Ukraine, there was a tribe called the Cossacks. They were horsemen, and led by a chief called, Bogdan Chmielnicki. This man had great ambitions and was planning revolution against Poland, when this was found out and the chief was imprisoned, but before his sentence was carried out, the king died. This began the Cossak rebellion. This led to massacres where both the nobility of Poland and Jews were killed and mutilated.

There was a Rabbi named Natan Hannover who witnessed the Cossack uprising in Ukraine. Because of the uprising he had to leave Zaslow, the town where he lived at the time. After his escape, he finally settled in Italy and wrote a chronicle of the Cossack massacre of Polish noblemen and Jews called, Abyss of Despair. He wrote about 14 different cities where these massacres took place and the atrocities that happened there against Jews during the massacre.

Katja Grether

Class of 2019

Museum of the History of Polish Jews- 1600-1800

POLIN presents an interactive and immersive history of Poland’s Jewish community. In the museum’s first few galleries, the displays presented tend to focus on specific objects, like a coin minted in the thirteenth century. As the museum’s timeline moves closer to the present, however, the focus is shifted towards spaces and towards communities as a whole.

One of the first rooms in this section of the museum shows the visitor a view of a seventeenth or eighteenth century Jewish community. Different “buildings” are set up to give an idea of the layout of a typical town, and animated drawings from the time period are projected onto the walls. Personally, I found this interesting to contrast with the same effect intended in the Rynek Underground museum in Krakow– while POLIN animated drawings, the Rynek museum had a looped film of actors in period dress portraying a typical medieval scene. I’m not sure which I liked better; the actors made it easier to picture the space, but the animations really gave POLIN’s space a unique atmosphere.

POLIN also presented reconstructions of important spaces– including the throne room in the Warsaw Royal Castle, which we had seen just a couple of days before, as well as the inside of a synagogue located in the town of Gwoździec. These reconstructions were some of my favorite aspects of the museum, especially since so many important Jewish historical sites in Poland no longer exist (at least in their original forms). To see an object or document, like the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, is one experience, but to see it in at least semi-context in the reconstructed throne room is an entirely different memory.

I know that this post has kind of turned into museum design reminiscing on my part, but I found POLIN unique and affecting not only in the way that it was set up but also in its existence itself. These environments– especially those from the late eighteenth to the turn of the twentieth century– are reconstructed with so much care and such a sense of near-nostalgia that the visitor (or this one, at least) enters the final section of the museum with a sense of dread. It made me think about how differently a museum like this would be handled in the United States– it definitely would not have opened so quickly, relatively speaking. This specific section of the museum, from 1600 to 1900, really reminded me of the differences in acknowledgement of the past, and I think POLIN deserves commendation for its portrayal of this time period. Here, the Holocaust is not portrayed as inevitable, and Poland’s Jewish community is shown as it was: a large and vibrant population that contributed so much to the culture and achievements of Poland as a whole.

Allison Dupuis ’18

Museum of History of Polish Jews— the 20th century

The POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews is located on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto and Warsaw’s prewar Jewish neighborhood. It is a narrative museum which presents a thousand-year history of Polish Jews. The museum was first opened on April 19, 2013. The museum’s Core Exhibition was opened in October 2014. It has become the most ambitious cultural institution in Poland since the fall of Communism. The museum features a multimedia narrative exhibition about the living Jewish community that flourished in Poland for a thousand years. The building, a postmodern structure in glass, copper, and concrete, was designed by Finnish architects Rainer Mahlamaki and Ilmari Lahdelma. The design refers to the thousand years of Jewish presence in Poland, which was broken by the Holocaust. The 170,000 square foot building includes an education center, temporary galleries, conference rooms, a children’s area, and Resource Center. It is the first museum that was dedicated to restoring the history of the civilization created by Polish Jews during a millennium.

Museum’s Core Exhibition is the soul of the museum. It occupies more than 4,000 square meters of the building. The exhibition, consisting of eight galleries, traces the history of Jewish community from their first appearance in Poland in Middle Ages until today. The long history of the Jewish people begins in the forests of the Poland of King Mieszko (960-992), where the first Jews decided to settle. It is a museum to discover how Jews first arrived in Polish lands, why they stayed, and how Poland became home to one of the largest Jewish communities in the world—— there were 3.3 million Jews in Poland before the Holocaust. While the Polish Jewish communities were largely destroyed, there has been a renewal of Jewish life since the fall of communism. The history of Poland is not complete without the history of Polish Jews. The story unfolds in acts and scenes as you walk. You will encounter those who lived in each period—— their words are quoted throughout the exhibition. As you walk on, you will also enter a salon, tavern, home, church, synagogue, or schoolroom. In addition, there are surprises in drawers you can open to see, screens and objects you can touch. Artifacts, photographs, documents, and films are shown throughout the exhibition. The reproduction of photos and objects makes visitors completely involved in the Jewish history.

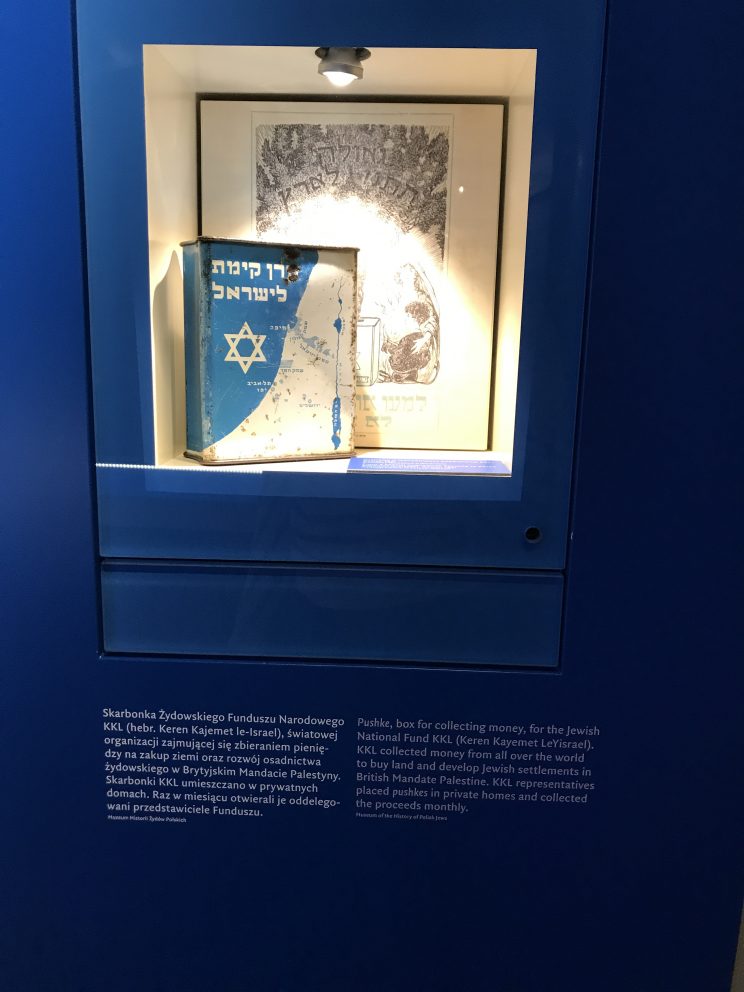

The story of the Holocaust focuses on the experience of Polish Jews. German repressions separate and isolate Jews and force them into ghettos. Diaries and documents preserved in the secret archive created by Emanuel Ringelblum and his team provide a unique perspective on the Warsaw ghetto and the Warsaw ghetto uprising. A bridge symbolic of the one across Chłodna Street offers a view from above of the so-called Aryan side. The view from below reveals the harsh reality of German terror against Poles, how the Polish underground state resisted the occupation, and how ordinary people responded to the Jewish fate on a spectrum from help to indifference and even betrayal. The German invasion of Soviet-occupied Poland marks the onset of mass murder by death squads and then in death camps. Barely 300,000 Polish Jews survived the war, most of them in the Soviet Union. The most urgent question for them was whether to stay in Poland or to leave. Many of them left for British Mandate Palestine, where they played an important role in the creation of the State of Israel. Those who remained in Poland helped to rebuild the country and Jewish communal life. Following the anti-Semitic campaign of 1968, only about 10,000 Jews remained in Poland. After 1989, with the fall of communism, there is a revival of Jewish life on a small scale. The enormous Jewish presence in Polish consciousness is seen in festivals of Jewish culture, Christian–Jewish dialogue, films and books, courses in Jewish Studies and many artistic projects. The Museum of the History of Polish Jews is also part of this story. Museum’s building faces the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes in Warsaw. At the monument, those who perished are honored. The museum presents a story of cooperation and competition, coexistence and conflict, separation and integration.

Qinyu Xu ’17

At the Museum of History of Polish Jews, it was broken down by the time they had arrived at Poland to the current activities taking place within the Jewish community. The museum explored the legislature side of the community interactions with the Polish government, Polish citizens, and interpersonal interactions within the Jewish community.

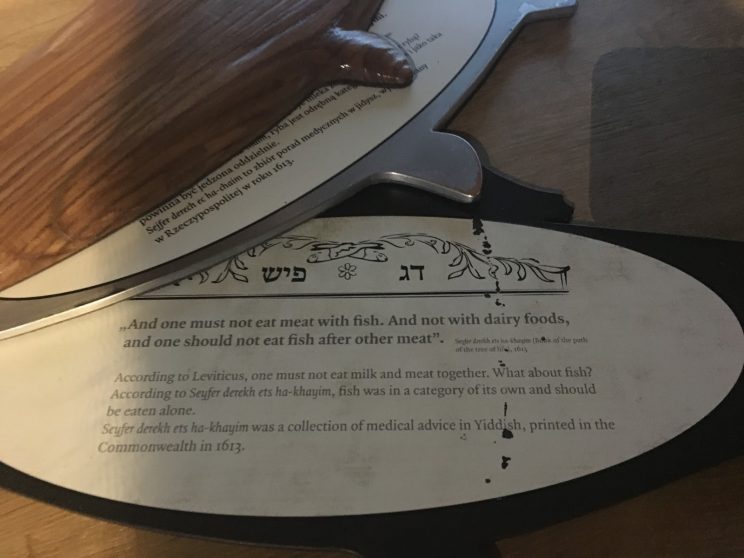

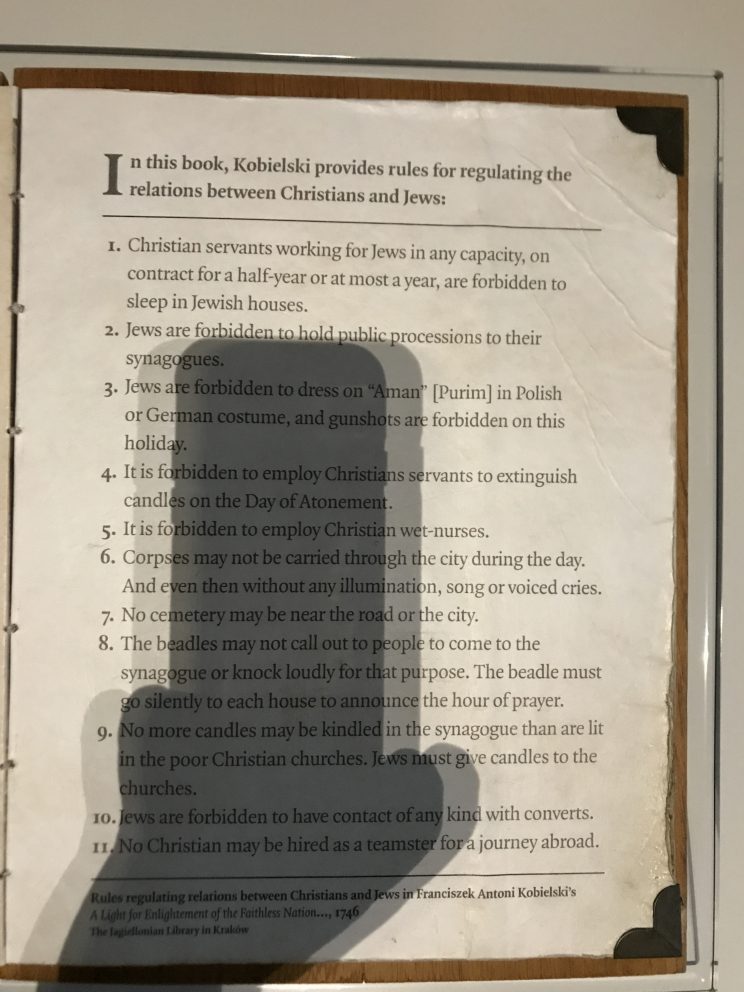

When the first groups of Jews arrived in Poland, they came exiled from London and Germany in the 10th century were they looked for a place to settle. With permission of the Polish King, the Jewish settlers were allowed to stay. With their settlement, there was a love and/or hate relationship with their Christian neighbors. Laws had been created to establish an order amongst both groups in hopes to protect the Jewish citizens. The Polish King ensured rights to work, practice religion, and owning property. However, if a Jewish member happened to live next to a Christian member there had to be a fence to separate both parties. Bishop Kobielski wrote some rules in how Christian and Jewish relationships were to be carried out. For example, “Jews are forbidden to dress on “Aman” in Polish or German costume…” or “The Beadles may not call out to people to come to the synagogue knock loudly for that purpose.” Furthermore, the Rabi’s were beginning to worry about its own members. Especially members living out in the countryside to far way from a central Jewish community to follow and respect the Sabbath day or Kosher eating. Therefore the Rabi’s created laws and punishments from further transgressions.

Advancing into the late 17th century, the Russian government took Poland’s land as their own, seizing property and killing people and forced conversions to Orthodoxy. More importantly, as the century is turning, it is noted that in1635 a town named Gozdzeic noted for the first time a Jewish presence in the town. Alongside that we see Pope Benedict XVI stated, “ that there should be not any persecution, slaughtering, or expelling of the Jews.” This theme of dishonorably accusing Polish Jews goes back to medieval times, which ties back into the love/hate relationship between the two groups.

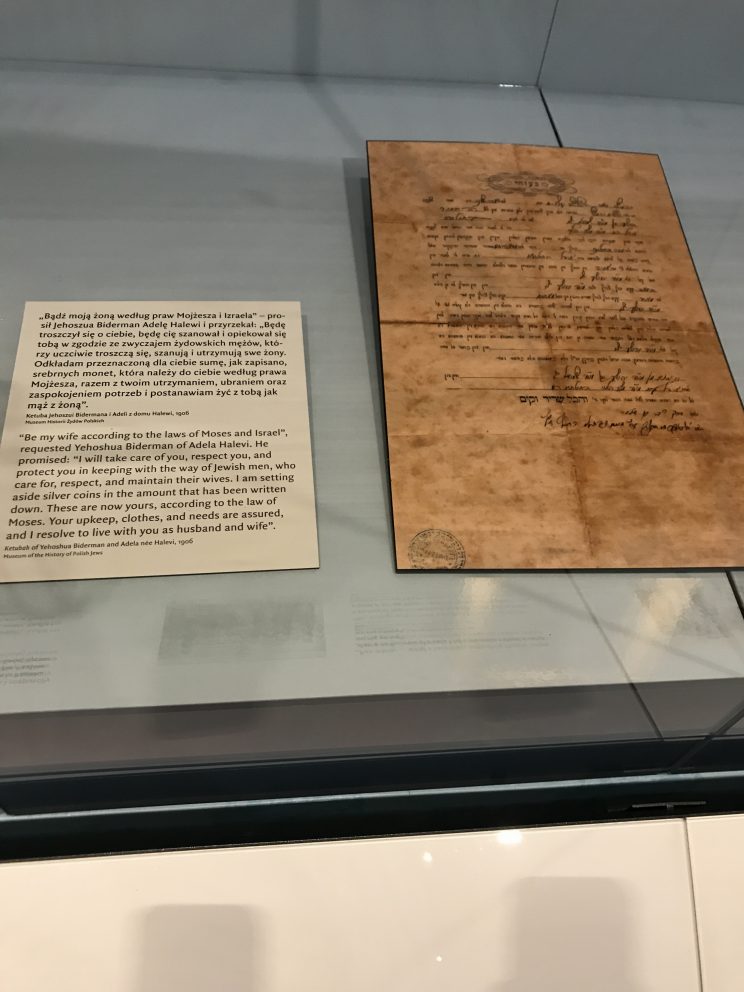

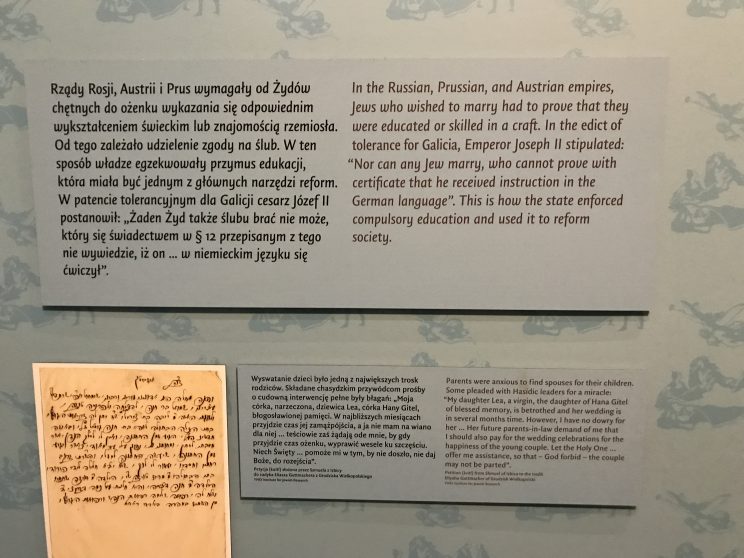

On the other hand, as the community politics is being held, legislation changing as the centuries turn the communal well-being of the Jew is flourishing. Each community Rabi was asked to keep records of the communities births, deaths, and marriages. Children all started with the same upbringing, which was learning Hebrew first then the Torah and later Polish and other class materials. Second, Jewish weddings remained very traditional as the years passed on. Young woman’s family had to provide a dowry to there. In addition, Jewish member who wished to be wed had to prove they were educated and skilled. Once wed, they signed a contract legally binding them. To the contrary, young Jewish girls and woman searched to become more independent at the beginning of the 19th century, due to strict households. Not caring that they were the lowest paid.

As war began to take over in the 1914 -1940’s, there was a great immigration of families to the US and other countries but overall the greatest hope that they could go back to Israel.

Karla A. Lopez ’17

Historic Jewish Structures

Poland is full of architecture and structures from different periods in history. Throughout the cities we visited, we saw many historical Jewish structures. These structures were and are important to the Jewish community in Poland. I was surprised that some of the structures were still standing after the war.

One of these structures includes the Old Synagogue in Krakow, Poland. This structure sits in the Kazimierz district of the city of Krakow. This district used to be dangerous and not a nice neighborhood, but now it is lively with restaurants and other things to do. The Old Synagogue is an Orthodox Jewish synagogue that is the oldest synagogue still standing in Poland. The structure was built in the 15th century and remains to this day one of the most important Jewish cultural centers in Poland. The original building was rebuilt in 1570 by the Italian architect Mateo Gucci. During the second world war, the Germans completely ransacked and looted the synagogue. During the German occupation, the building was used as an undercover magazine. Then, in 1956 the Old Synagogue was renovated and now operates as a museum that focuses on Krakow’s Jews.

All of the cities we visited also had Jewish cemeteries, all of which were incredibly historically significant. In Lublin, the Old Jewish Cemetery overlooks the Old Town and is entirely surrounded by a 17th century wall. The cemetery was founded around 1540. Many distinguished people of the Lublin Jewish community are buried there. Many of them have monumental and richly decorated matzevot headstones. During the German occupation of Poland many of the matzevot were demolished or were used for street paving. Now, the Old Jewish Cemetery holds some of the oldest and last surviving evidence of Jews in Lublin for centuries. In Krakow, the Old Jewish Cemetery is also known as the Remah Cemetery. The Remah Cemetery was built in 1535, and is now a historic site, thus inactive as a cemetery. The cemetery is named after Rabbi Moses Isserles, whose name is abbreviated as Remah. He is buried in this cemetery. During the German occupation of Poland, the cemetery was nearly all destroyed. Rabbi Remah’s headstone is one of the only still intact.

Poland is full of old Jewish Structures. The Jewish community that remained in Poland after the second world war are very proud of their history and heritage, and they work hard to keep their culture alive.

Lexie Dill (’20)